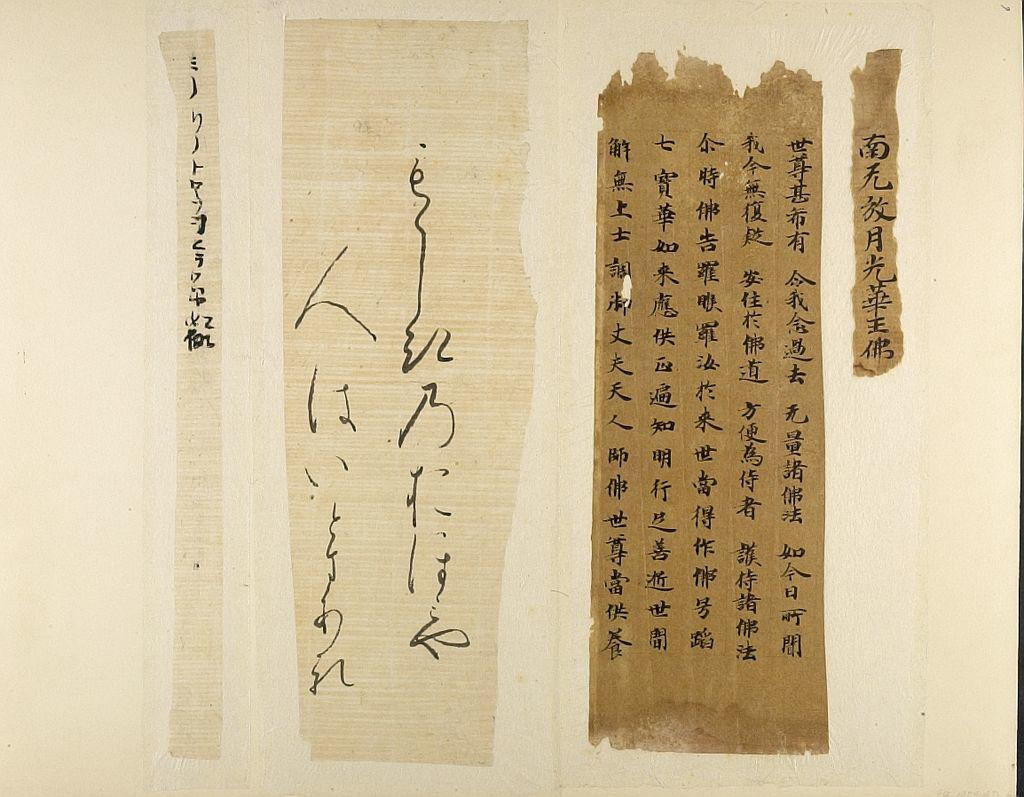

Students examine the texts, sculptures, and relics, once stored inside the celebrated thirteenth-century sculpture of Shôtoku Taishi.

Students examine the texts, sculptures, and relics, once stored inside the celebrated thirteenth-century sculpture of Shôtoku Taishi.

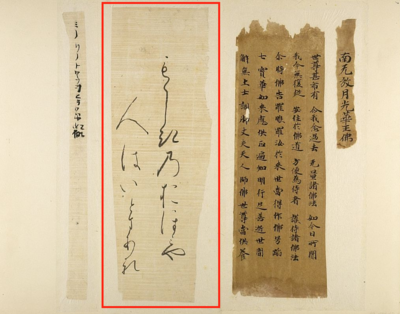

99.1979.4.D.6

Poem Fragment

The fragment largely consists of a makurakotoba (see explanation below). As such, there are actually two potentialities for the origin and meaning of this poem. Because this fragment only contains the majority of the first three lines (kami no ku 上の句) of a waka poem, and these lines are identical in Poems 1 and 3, it can be argued that the fragment evokes and embodies them both simultaneously.

Poem 1

- Man’yōshū 10, Various Spring Poems春雑歌: 1883 (early 8th, author unknown)[1]: Dai 題: Playing in the Field 野遊

- Akahito shū: 176 (late Heian period, attributed to Yamabe no Akahito): Dai 題: Playing in the Field 野に遊ぶ[2]

もゝしきの / おほみや

人は /いとまあれや

梅をかざして ここに集(つど)へる

Momoshiko no Are they so leisured

ōmiyahito wa The people of the great palace

itoma are ya Of the hundred stones?

ume wo kazashite Wearing the plum on their brows,

koko ni tsudoeru[3] They are gathering here[4]

Poem 2 (Intermediary Poem)

- Kokin waka rokujō 4: 3175 (c. 976-82, attributed to Kakinomoto no Hitomarō)[5]

もゝしきの / おほみや

人は /いとまあれや

むね(サクラ)をかさして ここにつどへり(クラシツ)

Momoshiko no Are they so leisured

ōmiyahito wa The people of the great palace

itoma are ya Of the hundred stones?

mune (sakura) wo kazashite Bedecking their chests (with cherry blossoms)

koko ni tsudoeri (kurashitsu) [6] They are gathering here/Passing time here[7]

The second version of this poem act as an intermediary between Poem 1 and Poem 3 via the use of furigana glossing that allows for the “incomplete” reading of both poems at once. The reading is “incomplete” because, while the glossing in line 5 allows for the double-reading of tsudoeru つどへる (in this case tsudoheri つどへり) and kurashitsu クラシツ, the glossing in line 3 only allows for an alternate reading of muneo むねを as sakura サクラ. Poem 2 remains an important part in the “genealogy” of the poem because it provides us with a snapshot that shows how it changes from Poem 1 to Poem 3 over time. The poem is also important because it is attributed to Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, and thus casts doubt onto any analytical conclusions based on authorship.

Poem 3:

- Shinkokin wakashū 2, Spring:104 (c. 1439, attributed to Yamabe no Akahito): Dai 題: None 題知らず[8]

- Wakan rōeishū 25 (c.1011, attributed to Yamabe no Akahito)

もゝしきの / おほみや

人は /いとまあれや

桜かざして 今日もくらしつ

Momoshiko no Are they so leisured

ōmiyahito wa The people of the great palace

itoma are ya Of the hundred stones?

sakura kazashite Wearing cherry on their brows,

kyō mo kurashitsu[9] They have passed another day[10]

Poem 3 is referenced in a poem by Genji in Genji monogatari 源氏物語 (The Tale of Genji, early 11th c.) in the Suma chapter.[11] Genji composes the poem when he turns twenty-seven in Suma and is lost in sad reverie:

いつとなく itsu no naku I miss them always,

大宮人の ōmiyahito no The people of the great palace

恋しきに koishiki ni So dear to me—

桜かざしし sakura kazashishi Ah, but see the day has come

今日も来にけり kyō mo kinikeri We wore cherry on our brows![12]

A Brief Note on Authorship

Poems 1-3 are by an unknown author or attributed to either Yamabe no Akahito 山部赤人 (active 724-736)[13] or Kakinomoto no Hitomaro 柿本人麻呂 (active late 7th c.),[14] two of the most famous poets from the Man’yōshū about whom very little is known. These poets are often associated. In the preface of the Kokinwakashū 古今和歌集, Ki no Tsurayuki 紀貫之 (c. 872–945) linked Akahito with the Man’yōshū poet Kakinomoto no Hitomaro 柿本人麻呂 (active late 7th c.), which led to their wide appreciation.[15] Akahito is considered to be one of the Thirty-Six Poetic Immortals (sanjūrokkasen 三十六歌仙). Akahito is also one of the Ogura hyakunin isshu小倉百人一首 (One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each, 13th c.), although this poem is not in the collection.

About the Makurakotoba “momoshiki no”

The first line of the poem, “momoshiki no”, is a makurakotoba or “pillow word.” A makurakotoba is a poetic epithet that modifies and enhances another word, often elevating a subject for the sake of the reader or audience.[16] Makurakotoba are often five syllables and are found in the beginning few lines of a waka poem. While makurakotoba were often used in the poetry of the Man’yōshū, many of the meanings have been lost over time, and are often in used in later poetry to achieve an archaic effect.

Momoshiki no means “built up of many stones or logs,” and most frequently attaches to ōmiyahito no (the people of the Great Palace). The phrase is commonly found throughout Japanese poetry, as can be seen in these examples:[17]

Man’yōshū 10: 1852 (author unknown)

ももしきの momoshiki no They are wearing wigs

大宮人の ōmiyahito no The people from the great

かづらげる kazurageru Hundred-stoned palace

しだり柳は shidari yanagi ha Seeing the drooping willow—

見れど飽かぬかも[18] miredo akanu kamo I tire not of its sight![19]

Man’yōshū 4: 694/691 (by Ōtomo no Sukune Yakamochi大伴宿禰家持)

ももしきの momoshiki no Oh, they are many,

大宮人は ōmiyahito no They who dwell in the great court

多かれど ōkaredo Of the hundred stones,

心に乗りて kokoro ni norite But one girl obsesses me—

思ほゆる妹(いも)[20] omōyuru imo She rides mounted on my heart.[21]

Initial Theories

(Will update by 10/24/16)

[1] Minemura Fumito, ed., Shin kokin wakashū, Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshū 43 (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1995), 50, poem 104, note 1.

[2] Information on the dai for the Man’yōshū and Shinkokinshū poems are found in Ibid. The Akahito shū was compiled in the late Heian period.

[3] Pak Pyŏng-sik, Man’yōshū makurakotoba jiten (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1990), 317; Kojima Noriyuki, ed., Man’yōshū, vol. 3, Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshū 8 (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1995), 44; Hitomaro no Kakinomoto, Akihito no Tamabe, and Ōtomo no Yakamochi, Hitomaro shū; Akahito shū; Yakamochi shū, ed. Aso Mizue and Kubota Jun, vol. 17, Waka bungaku taikei (Tokyo: Meiji Shoin, 2004), 170.

[4] This poem translation has been modified to mirror that of Edwin A. Cranston, Grasses of Remembrance, vol. 2, A Waka Anthology (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006), 766.

[5] Date obtained from Ibid., 2:553. Author attribution obtained from Minemura, Shin kokin wakashū, 50, poem 104, note 1.

[6] Kunaichō Shoryōbu, Kokin waka rokujō, vol. 1, Zushoryō sōkan 3 (Tenri: Yōtokusha, 1967), 178, , poem 355 (3175).

[7] Poem modified from that of Cranston, A Waka Anthology, 2:766.

[8] Minemura, Shin kokin wakashū, 50, poem 104, note 1.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Translation found in Cranston, A Waka Anthology, 2:766. For an English translation of the poem from the Wakan rōeishū, see J. Thomas Rimer, Japanese and Chinese Poems to Sing: The Wakan Rōei Shū, trans. J. Thomas Rimer and Jonathan Chaves (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 34, poem 25.

[11] Murasaki Shikibu, The Tale of Genji, trans. Dennis Washburn, 1st edition (W. W. Norton & Company, 2015), 283.

[12] Cranston, A Waka Anthology, 2:766.a

[13] For more about Yamabe no Akahito and translations of his poetry, see Haruo Shirane, Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 88–93.

[14] For more about Kakimoto no Hitomaro and translations of his poetry, see Ibid., 67–88.

[15] Edwin A. Cranston, The Gem-Glistening Cup, A Waka Anthology 1 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993), 299; Nihon Gakujutsu Shinkōkai. Special Manyoshu Committee and American Council of Learned Societies, The Manyōshū: The Nippon Gakujutsu Shinkōkai Translation of One Thousand Poems, UNESCO Collection of Representative Works. Japanese Series (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), lxxii.

[16] Robert H. Brower and Earl Roy Miner, Japanese Court Poetry, Stanford Studies in the Civilization of Eastern Asia (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1961), 12–13.

[17] In the Man’yōshū alone, there are seventeen poems with the first line beginning with momoshiki no, including six chōka “long poems.” See Pak, Man’yōshū makurakotoba jiten, 316–17, entry 431.

[18] Kimura Seiichirō, Man’yōshū, vol. 3, Koten Nihon bungaku zenshū (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1959), 8.

[19] My translation.

[20] Kojima Noriyuki, ed., Man’yōshū, vol. 1, Shinpen Nihon koten bungaku zenshū 6 (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1995), 345, poem 691.

[21] Cranston, The Gem-Glistening Cup, 436